By Dr Shane Ingrey

On the morning of Sunday 29 April 1770, as Lieutenant James Cook and his landing party came close to the shoreline at Kundell (the Dharawal name that Kurnell derives from), they heard the words “warra warra wai” being projected towards them. These words were accompanied by threatening gestures with raised spears by two Gweagal warriors. These same words and gestures were witnessed again 18 years later when the First Fleet sailed into Kamay (Dharawal word for Botany Bay) and then Sydney Harbour – it is clear from the original sources that they could only assume they were being told to ‘go away’. These uncertainties were lost when variations of these words appear in several early Aboriginal word lists, where they are simply said to mean ‘go away’.

Two Natives of New Holland Advancing to Combat Sydney Parkinson - State Library of NSW

It wasn’t until recently that Aboriginal people belonging to Kamay were given the opportunity to ‘tell our story, our way’, and a totally different perspective of these famous encounters started to emerge. The Gadhungal Research Group, whose members descend from those who watched Cook sail through the heads of Kamay and are leading Dharawal language reclamation in the La Perouse Aboriginal community, decided to challenge this assumption. This marked a continuation of the work of senior women of the La Perouse Aboriginal community who had been railing against the misrepresentation of their people since the 1980s.

A detailed review of historical sources, both Aboriginal and colonial, combined with existing cultural knowledge, revealed that “warra warra wai” did not mean ‘go away’. Rather, it was a phrase entrenched in local Dharawal ontology or dreaming, which contained stories of the arrival of animals on a ‘barangga’ (big vessel also the name for island), and the return of guwinj (spirit or ghost) from the afterlife, travelling back in low-lying clouds. Looking at these events through a spiritual lens we came to understand some of the spiritual reasoning in interpreting those events.

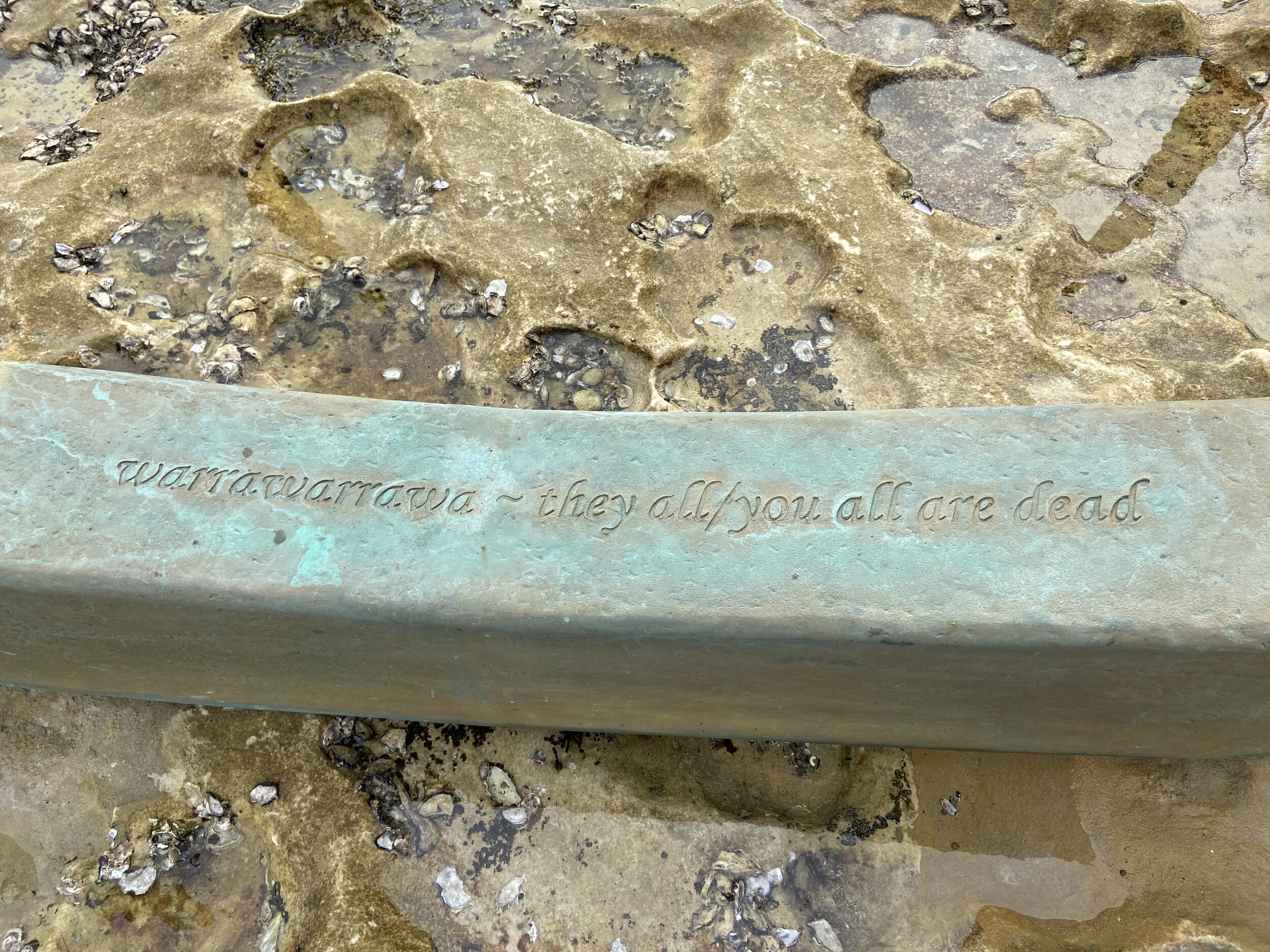

When we look at the phrase “warra warra wai” from a Dharawal language perspective it literally translates to “you’re (they) all dead”. In Dharawal ‘warra’ sometimes spelt ‘wara’ means dead and when the words is repeated it is emphasising the large amount or significance. There are Dharawal words associated with the colour white, which incorporate the language term ‘warra’, such as djilawarawara meaning white and warrabugan meaning whiting (fish). There are also cultural linkages between the word warrawarra and objects that are associated with the colour white. This includes the iconic Australian flower the waratah (waradha in Dharawal). In a Dharawal Dreaming story, associated with Dharawal women, the waradha was originally white, and was stained red with the blood of the wonga pigeon turning the name of the flower to managuwang.

Extract showing wuraoranbala (warawaranbala) from ‘Specimen of Native Australian Languages’, Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland 1874

The misinterpretation of warrawarrawa, the verbal meaning was assumed from the geastures, is simply one of many language and cultural misinterpretations. When people from outside our community, with limited cultural knowledge, look at early colonial manuscripts such as William Dawes's , to assist in reconstructing language, culture and customs of Sydney, it seems the perpetuation of misinterpreted information continues. It is understood Dawes, who was an officer and scientist with the First Fleet, was not a trained linguist, received information from numerous sources including settlers and officers and had limited understanding of our culture and customs.

Today we use Dawes manuscript to give us language and cultural information from a certain point in time, however as this was interpreted through a western lens some of the information had been misinterpreted. When we look at it from our cultural lens we are able to interpret more accurately. Dawes documented words like ‘Nangamai’ as ‘to dream’ however nangama in Dharawal translates to ‘he/she/it is sleeping’. He wrote that ‘Beeanga’ meant father and is used by people trying to reconstruct the ‘Sydney Language’ but in Dharawal biyangga means the most senior person (male) of a certain group of people. Our old people used biyangga to describer senior status people including Jesus Christ. These terms are used correctly within families belonging to the La Perouse Aboriginal community.

warrawarrawa - they all/you all are dead inscribed on the Commemorative Installation for the 250th Anniversary of the Endeavours’ arrival in Kamay (Botany Bay). Previous works installed promote the misunderstood interpretation of ‘go away’.

These misrepresentations are also compounded by the modern interpretations of the geographical area of ‘Sydney’. Colonial Sydney was centred around what is now the CBD area of Sydney with places such as Botany, Vaucluse and Parramatta falling outside the boundaries of Sydney. Today people read early colonial documents and interpret Sydney as we know it now, being the Greater Sydney Region.

For far too long it has been accepted that the only valid sources of Aboriginal language in Sydney are the conjectures of foreigners trying to understand a deeply complex culture. In this case, trying to interpret a language and culture that has been continually developing from deep in time within a short timeframe. We know these are valuable records and accounts of course, but they are not the only sources or perspectives we can draw on.

When we go beyond the British interpretations about the words such as warrawarrawa, biyanga and nangama; when we consider information from those that are best placed to give it, a very different and more plausible picture emerges. The viewpoints from Europeans makes much more sense when interpreted from a local Aboriginal perspective and this can only complement and enhance what was documented all those years ago.

Note to reader. The term ‘Dharawal’ is used to describe a language, people or tribe and plant. Over time it has been documented as Turuwul, Thurruwul, Thirroul, Tharawal and Dharawal. It was described in the 1860’s as “the language of the now extinct tribe of Port Jackson and Botany Bay (from John Malone, a half-caste, whose mother was of that tribe)” Dharawal was the first known language name identified in the greater Sydney area. It is also the name of the native plant commonly known as the cabbage tree palm and is the overarching spirit ancestor or totem for all Aboriginal people and clan groups who belong to and speak Dharawal. It is always taught that your language and country go together and the people speaking it belong to that country.